Photo: Clara at home, July 31, 1996

Steve J. Sherman. All rights reserved.

I remember my dad, Bob Sherman, once responding to someone's remark about how strange an instrument the theremin is; having grown up as the nephew of Clara Rockmore, he wondered why they would think it strange. "After all, didn't everyone's aunt have a theremin in her home?"

They would have, had RCA had its way back in 1929… According to Albert Glinsky's authoritative book, "Theremin, Ether Music and Espionage," RCA's E. A. Nicholas said: "Any one who is able to hum a tune, sing or whistle is likely to play the RCA Theremin as well as a trained musician." (pg 101 - see footnote #13). An RCA promotional brochure trumpeted that, "Anyone can begin to play it on the same footing with the finest cellist, or pianist, or other instrumentalist in the world... it is the easiest of all instruments to play!… It is destined to be the universal musical instrument; people will play it as easily, and naturally, as they now write or walk." (pg 105 - see footnote # 25).

Well, as things turned out, everyone's aunt did not end up having one in her home, and if she had, most would not have been able to play it anyhow. But for dad it was still perfectly normal to have an aunt with a theremin, and of course, as the sister of his mom Nadia Reisenberg, it was just expected that she would play it exquisitely well.

By the time I came around, I too assumed it was perfectly natural for one's great-aunt to have a theremin in her home, and it sure sounded easy when she played it… I also assumed it was normal to go out to see one's grandmother playing piano recitals in really big rooms, such as Carnegie Hall… And for one's elders to play music together at family parties or just while enjoying a quiet afternoon visiting one another…

As a kid, visiting Clara was always a treat… After walking down the long hall to her Parc Vendome apartment, Clara would greet us at the door beaming, always beautiful, charming, graceful and elegant, with kisses and hugs and histrionics for all. We'd be invited to sit around her large square glossy-black table, and sip tea with lumps of cubed sugar (she always put the cube on her tongue and then sipped) and munch on La Vache qui Rit cheese squares on Ritz crackers, and other assorted cookies and cakes and Clementine oranges. We'd have animated conversations about all sorts of wonderful things, and at some point, Clara would usher us all into the living room, and once seated, she would step up to her theremin, dwarfed by the large diamond shaped speaker behind her, and with the painting of Paul Robeson as Otello off her right shoulder…

She would turn the instrument on, let it warm up with a few small squeaks and blips, and suddenly that magnificent sound would burst forth, sweeping aside any errant air molecules in its path… Suddenly she was larger than life, with that intense far-away look in her face as she played – staring down the ages, commanding the soul with other-worldly force. I was enraptured, enveloped in velvet and electricity, watching the tea in my cup ripple with the sonic waves. Often I came over with Nadia, or Nadia and Newta together (the three Reisenberg sisters, or as they referred to themselves, the Romanov sisters), and then it was a real concert with Clara and Nadia sallying forth…

I mean, wasn't this every kids experience visiting with one's grandma and great-aunts?

Clara would always let me try my hand(s) at it. Happy Birthday was a great song to work on, since I knew it so well and it was so "easy." But it had an octave jump that distinguished between the amateurs and the rank amateurs… Alas, I was a rank… I was never able to get that song (or any other) to the point where it sounded like what it sounded like in my mind. A few years later, my younger brother Peter was able to get it to sound like something, and I was amazed, jealous, and ever more curious…

How could I know how lucky we were? I remember laughing at the mid-1960's sitcom "The Munsters" --- I always loved that they acted as just any normal family, and had no clue that they were any different. But it never occurred to me that there was any connection to us… We were perfectly normal…

Only when I became a teenager did I start to understand that in fact this was not normal, but outrageously weird. But in the best sense of those words!! It became something to talk about, a source of mystery and of pride – if only I could explain the damn thing to my degenerate musician hippie friends… high frequency electromagnetic fields, beat frequency oscillators, series resonant circuits… YIKES. Hey man, like just wave your hands in the air, man, and like beautiful music just comes out, man…

As a teenager I started visiting with Clara on my own, and we'd get into deep talks about art and philosophy and politics. She would regale me with stories, and she always wanted to have the latest up-t0-date gossip on my love life…! She was always so involved with family and especially the younger generations, and always over tea, with La vache qui rit on Ritz crackers…

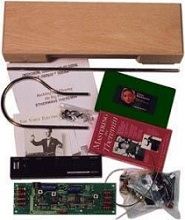

In 1977, Clara's first record album was released -- titled simply "Clara Rockmore, theremin" and subtitled " 'premiere artiste' of the electronic music medium, with Nadia Reisenberg, piano." This vinyl recording by Bob and Shirleigh Moog finally allowed people to hear Clara's true virtuosity. And I was finally able to explain coherently this phenomenon to my friends…

When that same album was re-released a decade later as a CD, it took on the name "The Art of the Theremin" -- by then I was savvy in the ways of the world and the market, and knew how incredible it was for Clara to have this small renaissance. For Clara was totally devoted to bringing this instrument into its own, encouraging musicians to take it up and play it, leading by example and then stepping aside and letting 'em rip.

But this was only the beginning. Soon thereafter, Steven M. Martin came along and proceeded, through his magnificent film "Theremin, An Electronic Odyssey," (1994) to catapult Clara back into world fame, back into the spotlight that she had so enjoyed decades earlier, and give her the glory that she so deserved.

Of course, Clara didn't want the fame – she wanted recognition, and she wanted to inspire others, but fame by itself was empty, annoying and bothersome at best.

Her phone would ring off the hook, requests came in from around the world for her to perform, or be interviewed, or do this commercial or that stunt. Indignant as she was with all at this media hoopla -- "what do they think, I'm still a spring chicken?" -- she was nonetheless delighted when from within this circus would emerge connections with musicians and others who were deeply interested in and moved by the theremin and its potential for, as she put it, "the right reasons". And for this, she was deeply proud, and happy, and grateful.

I must interject here that Bob Moog was always so sweet and supportive of Clara, always with a big smile, a bear hug and his tools ready and waiting for her call. And Steve Martin gave her much more than just fame and glory – he became a close and trusted friend, as close as family, and to the very end, was loyal and devoted and loving…

It's been quite an incredible odyssey indeed, since Clara's death on May 10, 1998. And here we are today, March 9, 2011, celebrating Clara's life and legacy on what would have been her 1ooth birthday. Her centennial. How cool is that!!

Like Joan of Arc, Clara barely exceeded 5 ft. in height (unless you counted her hair) and never quite reached 100 lbs. in weight, yet she was larger than life, and her stature just kept growing. With Steve's movie, Albert's book, Bob Moog's recordings and the availability of his theremins, the strangeness was fast becoming less strange…

In 2006 dad tirelessly worked to re-master and remake Clara's second CD recording with her beloved older sister Nadia: "Clara Rockmore's Lost Theremin Album." Clara would have been thrilled with the sound quality, and so very proud of this recording. And the best news is that there may yet be more CDs to come…

But the biggest news is… I'm thrilled, proud and humbled to announce to you here and now that THE definitive and oh-so exhaustive biography of Clara Rockmore is being written by David McGill – thereminist, author, Grammy Award winning principal bassoonist and soloist with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (and before that the Cleveland and Toronto Symphony Orchestras), and supremely nice guy. David's first book was "Sound In Motion; A Performers Guide to Greater Musical Expression" (Univ. of Indiana Press, 2009), and his forthcoming book on Clara (in two parts: one an in-depth bio and the other a comprehensive study of her technique) is moving full steam ahead. He hopes to complete this tome within the next two years, and I have to say, from the sneak previews I've seen, it's going to be an unparalleled blockbuster! I mean, David's sleuthing has dug up things about Clara that none of us in the family even knew.

Want a teaser? David just emailed me the following -- just for you!!

What drew me to Clara Rockmore was her musicianship. Through her intelligent musical phrasing, she immediately took her place on the same solid ground as my other musical heroes. I did not make allowances for her playing because it happened that she played an instrument as difficult, or as strange, as the theremin.

Through the decade following that night, I was privileged to perform at Carnegie Hall as principal bassoonist of three great orchestras, the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, the Cleveland Orchestra and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. I never realized that when I was in New York I was performing only three blocks from the home of Clara Rockmore. I never did the research. And I never met her.

Now I am trying to make up for that oversight by researching every facet of the life and musical career of little "Klara Reisenberg" and her amazing family. What I have unearthed in just less than two years has amazed me. In some way I am beginning to feel as though I know Clara Rockmore.

What are the first few "facts" one learns about Clara? She was born March 9, 1911. She was Lithuanian. And her maiden name was "Reisenberg" (pronounced "RIZE-en-berg).

Here are the real facts regarding these basic pieces of information: The March 9 birthday which we celebrate now was not the date she celebrated with her family in Russia. According to the old "Julian" style calendar, she was born on February 24th, 1911. Only after her arrival in America did she and her family update their birthdays by moving them thirteen days later, in accordance with the "Gregorian" calendar used in the Western world. (The Gregorian had been adopted by the new Soviet government in 1918, but it was not universally recognized by the populace until years later.) Clara was also never a Lithuanian citizen. She was born and raised in formerly Lithuanian territory, but Vilnius had been a part of the Russian Empire since 1795. She never learned the Lithuanian language. She and her entire family were Russian citizens "by birth" (as printed in her later publicity material). Additionally, during her early years in America, Clara was officially considered a citizen of Poland because of that country's domination of Vilnius. And Clara's family name? -- She and her family pronounced it "RAYZ-in-berg."

These are not earth-shattering revelations, but they reveal that there is much to discover about this woman whom we feel we already know.

Another well-known myth about Clara Rockmore has also been dispelled. At four-and-a-half little "Klara" was admitted to the violin class at the Saint Petersburg Imperial Conservatory of Music (by that time renamed the "Petrograd" Conservatory). This is a fact. But she never studied with the great violin teacher Leopold Auer while in Russia. Her teacher during her two-and-a-half years at that school was the now-forgotten Maria Gamovetskaya. Clara later said that "I really didn't need Auer" at that early point in her musical development. Once in New York, Clara studied from 1922 to 1926 with the great Franz Kneisel at what was later to become the Juilliard School. Then, at fifteen, in 1926, the time finally arrived for her to study with Auer. He, too, had sought refuge in America. She studied with him privately for two years and then at the Curtis Institute for an additional year until "the tragedy" of having to give up her violin studies struck in 1929.

And what was the cause of her having to give up the violin? She was not, as often asserted, a victim of "bone problems brought about by childhood malnutrition." After consultation with a leading authority in performance related disability, it is clear beyond all reasonable doubt that the symptoms Clara reported about her bow arm conform exactly to the prosaic diagnosis of severe tendinitis.

Revelations about her malady; her first teacher; her birth date; even the pronunciation of her family's name were just the beginning. Scores of discoveries awaited.

Another surprise lay in the identity of an nineteen-year-old cellist studying at the same school when Klara was admitted in 1915. His name ... Lev Termen. Incredibly, their schooling overlapped by two years. Lev may even have heard of the "wunderkind" Klara while studying at the Petrograd Conservatory. Further research may yet reveal the answer to this question.

To whet your appetite for more: I have recently located a hitherto unknown recording of twenty-eight-year-old Clara, from 1939, in pristine sound. For more details, you will have to wait.

Anyone wishing to share information with me about his or her own experiences with Clara Rockmore is welcome to email me at dmcvegan@juno.com. No detail about her is too small.

Clara is being honored, feted, discussed, debated, played to, and fondly remembered around the globe as one of the greatest musical pioneers of the 20th century, ushering the electronic music movement from its infancy to modern maturity. She remains to this day one of the few who have truly mastered this instrument, and her theremin voice remains the ultimate inspiration, the definitive example, the goal to be ever sought and like Mt. Everest, to be ever conquered.

Today there are many amazing thereminists around the world and more and more musicians are taking the theremin into their homes and their hearts, their music spewing forth on YouTube for all to marvel at (or run from). Internet forums like Theremin World, Levnet, and Theremin Vox, to name just a few, are popular and thriving.

No one would have been more thrilled and proud to see this than Clara. And no one would have rooted for "the next Clara Rockmore" to emerge than Clara herself… For by the end of her life, Clara knew well that her musical legacy was solid, that her musicianship spoke for itself and would stand the test of time, but for someone to come along and take it the next step, a notch higher, would be, for Clara, the greatest of all her accomplishments. For indeed, a weird instrument that was always ahead of its time and apparently destined to stay ahead of its time, would finally find that its time is all time, and thus its journey continues into the future, with no limits…

Happy 100th birthday Clara. We love you and miss you madly, but you have left this world a far better and more interesting place than you found it, and as long as music can be made from thin air, you will always be here with us.

Steve J. Sherman